Revisiting the Powell Memo: has the judicial system become irredeemably marred by ideological bias?

The Rittenhouse murder trial and the Charlottesville civil case have brought the question of judicial impartiality back into full relief, the question being whether the courts will be an effective means for addressing ultra-right violence. Many suspect not.

On September 12, 2021, Amy Coney Barrett delivered a speech at the University of Louisville’s McConnell Center in which she expressed concern at the rising impression of the Supreme Court as partisan. Barrett asserted that judges must be “hyper vigilant to make sure they’re not letting personal biases creep into their decisions, since judges are people, too.”

Given the circumstances of Barrett’s confirmation, led by Mitch McConnell, many might have found her comments on the importance of impartiality in that particular setting a tad suspect.

At a time of dramatic polarization in society, can judges who are people too be impartial? In matters of social justice, is final appeal to the rule of law no longer a viable option?

Lady Justice

In one hand Lady Justice holds scales that are balanced, in the other she raises a sword unsheathed, and over her eyes a blindfold is tied. The scales represent objectivity: she will hear both sides out and weigh the arguments and evidence in an open and fair manner. The blindfold represents impartiality: she will make her decisions through a veil that causes her to leave her own subjective views and biases aside. The sword represents the force of law: with objectivity and impartiality on her side, her decisions will bind us, and we will come to voluntarily respect and obey the rule of law.

In the name of objectivity, judges will adhere to and promote procedural fairness in relation to the matters they hear. In the name of impartiality, judges will exercise substantive fairness in arriving at decisions that impact the parties before them and society in general. Procedural and substantive fairness are the grounds and conditions upon which a people governed in a liberal democracy come to view themselves as morally bound to abide by the law.

When a court of final appeal hears a case involving significant inequalities or unfairness in society, the justices unavoidably promulgate their views on what substantive fairness means in that society.

Judges Have Wide Discretion

Judges interpret the law in accordance with a number of principles that have developed over time, primarily via the common law. Judges are often construed as prudent or interventionist in their approach to interpretation.

Legal positivists insist that there is the letter of the law and nothing more. Accordingly, judges must not make reference to anything other than relevant statutory and case law.

Ronald Dworkin, perhaps the most notable American philosopher of law, challenged this view. He posited an interpretive ground upon which the letter of the law is based. Good law is law that is interpreted with an integrity that is consistent with the overall values and principles of the society that the law binds. Depending on the circumstances, a judge may stick to the letter of the law, or be justified in referencing public morals that support his or her decision.

The ability for judges to pick and choose principles of interpretation, take a restrained or progressive approach to interpretation, stick to the letter of the law or reference social mores, combine to result in an enormous degree of latitude when it comes to exercising judicial discretion.

The Powell Memo

How did ideological bias and ultra-right conservatism come to infect the highest court in the land?

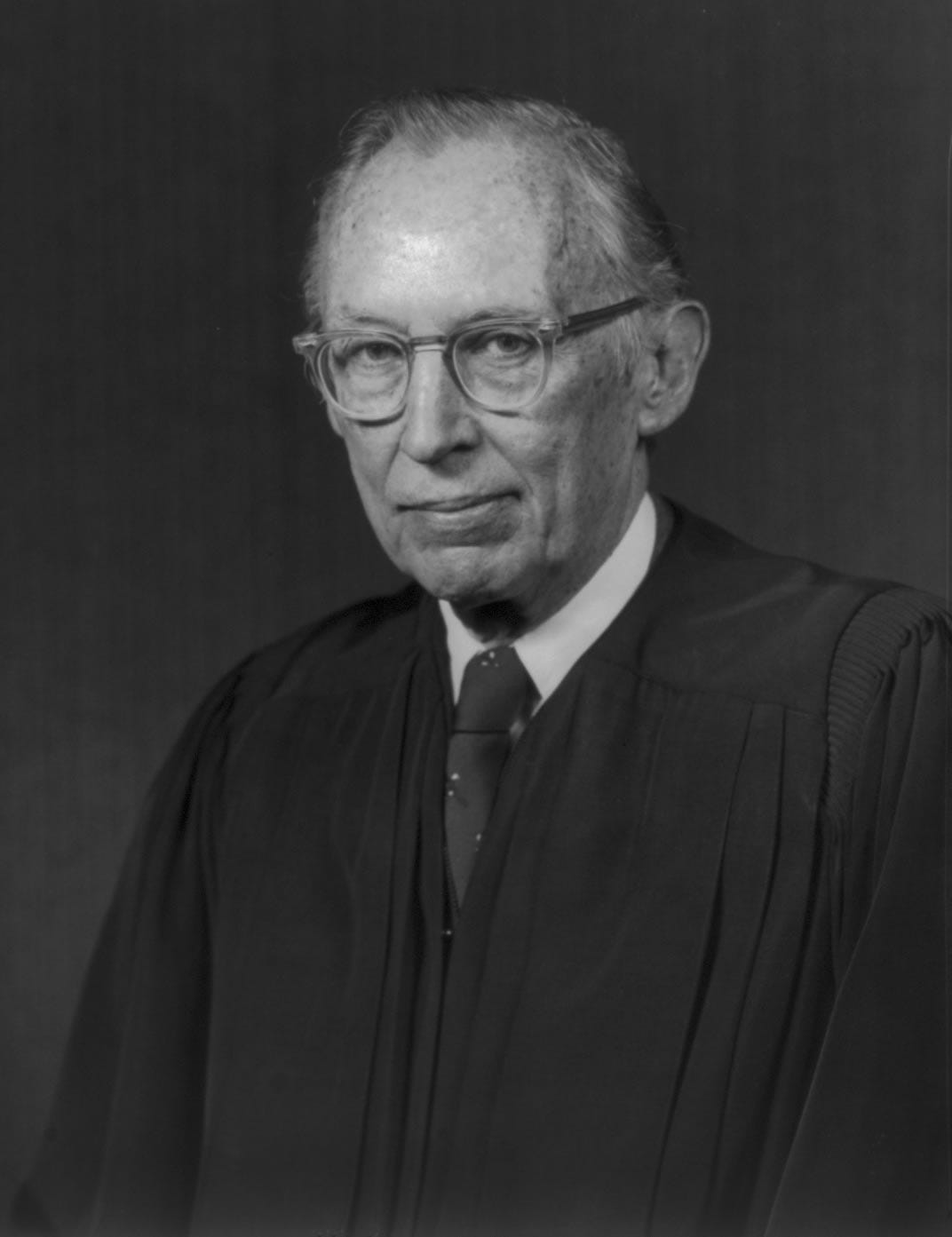

Lewis Powell Jr. was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Nixon and was an Associate Justice from 1971 to 1987.

Prior to his confirmation he wrote what has come to be known as the Powell Memorandum, formally entitled, “Attack on the American Free Enterprise System.”

The memo outlines how business interests should retake America. Powell urged corporate America to be more aggressive in shaping society’s views in relation to business, government, politics, the law and education. Powell espoused a minimally regulated America, and accordingly, the document has become a blueprint for the rise of American conservatism and right-wing libertarianism.

The most disquieting voices joining the chorus of criticism come from perfectly respectable elements of society: from the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians. In most of these groups the movement against the system is participated in only by minorities. Yet, these often are the most articulate, the most vocal, the most prolific in their writing and speaking.

Powell advocated constant surveillance of left or liberal tendencies in society, and active intervention in schools and universities. And in relation to the courts he had this to say:

American business and the enterprise system have been affected as much by the courts as by the executive and legislative branches of government. Under our constitutional system, especially with an activist-minded Supreme Court, the judiciary may be the most important instrument for social, economic and political change.

The Powell Memorandum was a manifesto that ushered in an era of intense lobbying of politicians and a heightened focus on ideological appointments to the Supreme Court. From that point on, the Supreme Court was viewed from the right as an effective means or tool to further a conservative political agenda.

Studies of the impact of ideological background on Supreme Court decisions have been conducted. The results are mixed. There are a number of cases in which a consensus is found among justices, notwithstanding ideological divides. However, there are a significant number of cases in which decisions are split in a manner consistent with ideological preferences.

Suffice it to say, there is enough evidence to suggest that justices, like most people, cannot leave their subjective views at the door. The possibility or ideal of impartiality is indeed compromised via intensification of ideological appointments to the bench.

Nietzsche and the Drives

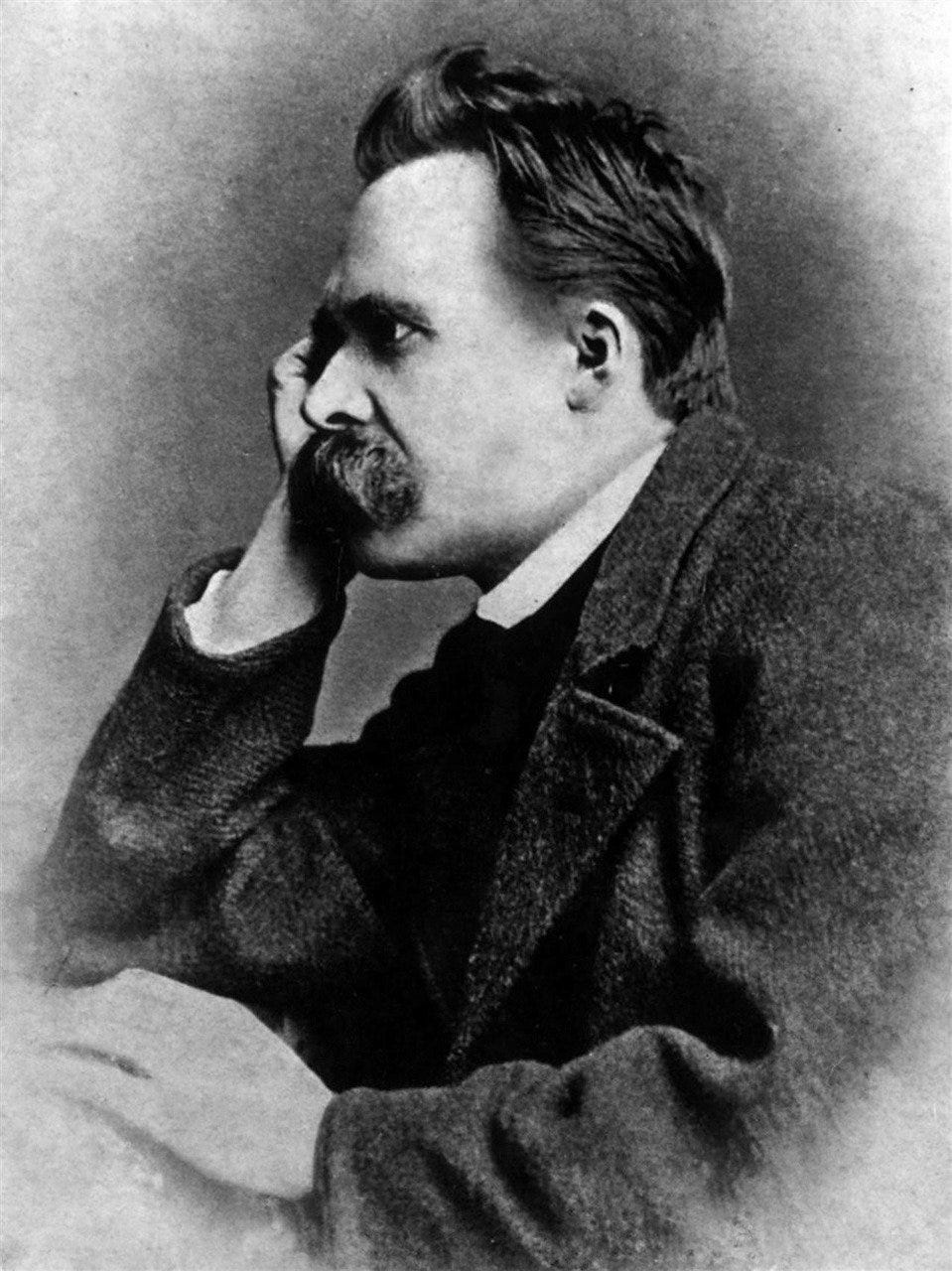

What would Nietzsche have made of the concept of impartiality?

Nietzsche asserted that “there are no facts, only interpretations.” There are no objective truths, only perspectives. It is our drives that interpret the world.

Each of us has multiple perspectives in relation to the world because there are a multiplicity of drives within, competing and often contradicting each other.

Within ourselves, we can be egoistic or altruistic, hard-hearted, magnanimous, just, lenient, insincere, can cause pain or give pleasure.

There is no struggle of reason against the drives. Reason is nothing more than an ordering of the drives.

The drives compete internally, and at each juncture when a decision is made one drive has overcome the others. Nietzsche asserts that we falsely identify this winning drive with a sense of objectivity when there is none. Reason is borne of desire.

If Nietzsche is correct, then there is no possibility for impartiality in the sense of detachment. One cannot don the blindfold of impartiality if the very process in which decisions are made is governed by subjective desire. Impartiality then, is nothing more than a red herring.

Consider this in relation to the process of adjudication. The principles chosen and approach taken all depend on which drives won out the day. Picking and choosing principles of interpretation, one can easily obtain either of two polarized results, all within the constraints of the common law. The breadth of legal discretion inherent in the interpretive process assures nothing more than a shield justifying the decision made.

Competing drives are like a roll of the dice, but they are also likely linked to ideas to which over time we have developed an emotional attachment, eg., emotional views one might have regarding race. In such matters, the ancient brain short circuits the modern one: the cerebellum takes over, the cerebral cortex rendered slave to and workhorse for the emotions.

Is it not reasonable to assume that justices who are real people too are not also subject to these dynamics?

If this is true, then we need to take a long and hard look at impartiality and weigh up just how real it is as a legitimate judicial ideal. If it is premised on false grounds, then is it not better to end the charade and admit that courts of law are politically charged?

Polarization

Analyses in relation to the correlation of political ideology and Supreme Court decisions span a period prior to the explicit polarization in society in which we currently find ourselves. What will the record be for impartiality in the Supreme Court in the coming years, post-Trump era polarization? How will polarization impact justices with wide discretion, albeit responsible to general principles of legal interpretation and the overall public moral setting in which they must arrive at their decisions?

Ideological divides in society are not only related to business interests, as perhaps they were in Powell’s eyes at the time of writing his memo. Ideological divides permeate every aspect of American life. Supreme Court justices increasingly will be asked to consider cases that directly impact social justice in society. They will be forced to confront within the full range values and beliefs they hold close to their hearts.

In a society divided, which public morality informs the integrity of law’s empire? If there are at least two polarized public moralities, how is a Supreme Court justice to decide? There can be no alternative other than reliance on subjective preferences, together with the construction of a reasoned opinion to back up the decision.

Most would agree that the flag flying over the courthouse means something. It reflects the common ideals and beliefs of a nation and imposes on the court a moral duty to adjudicate in a manner consistent with those ideals. But if those ideals are divided and polarized, one might argue that a Supreme Court justice has no real choice but to follow the ideological grounds for their nomination and confirmation.

What Next?

Judicial impartiality is arguably a fiction at the best of times. Desire sparks thought, is the force behind thought. A reasoned decision does not appear out of thin air and is not arrived at by the application of transcendent, supernatural faculties of reason. Reason springs from desire.

No doubt, there are many good judges who make just decisions. But they make those decisions as whole persons, because they are good people, not because they are good judges endowed with a higher level of impartiality than others.

The court has become ideologically tainted, and as polarization in society continues, this will likely further cripple the court in arriving at decisions that are just for a society divided.

If the Supreme Court’s role is in large part a check on the power of the legislative and executive branch, the court’s ability to fulfill this role is severely compromised by polarization in society and ideological appointments. In this scenario, recognition of the limitations of impartiality makes it debatable whether the court can continue to effectively perform its role as a check on the will of the majority, a guardian of the rights of individuals or groups, and protector of the rule of law overall.

We have seen this in history. Once a polarized society devolves into an anti-democratic or fascist regime, the courts become powerless. History proves that the courts just end up following the will of a dictator.

Puppet courts are something we think of in relation to rogue states. But one might argue that we are taking our first steps towards this scenario by blatantly usurping the court’s impartiality via ideological appointments in a polarized society.

On the other hand, perhaps we should stop clinging to an ideal of impartiality and recognize that the court is a political tool, full stop. After all, courts are in some ways inherently undemocratic — our first clue should have been that justices are appointed for life.

…

Thanks for reading!

Tomas

Please join my email list below.

Excerpt from my forthcoming book, Becoming: A Life of Pure Difference (Gilles Deleuze and the Philosophy of the New) Copyright © 2021 by Tomas Byrne.

Leave a Reply